SFC Kenneth E. Price, Jr.

Quartermaster Professional Bulletin – Spring 1994

Quartermaster water support during Operation Restore Hope in Jilib, Somalia, reinforced one non-commissioned officer’s viewpoint of the Army’s need for strict sanitation requirements with water purification equipment. In this article, SFC Kenneth E. Price, Jr., tells about deploying from the schoolhouse at Fort Lee, VA, to a nation torn by civil war: He is an instructor in the Water Training Division, Petroleum and Water Department, U.S. Army Quartermaster Center and School, Fort Lee, VA. SFC Price was the noncommissioned officer in charge (NCOIC) of the “Logistics Support Activity in Somalia” described in an article by CPT S. Carter Corsello in the Winter 1993 Quartermaster Professional Bulletin.

I deployed to Somalia on the coast of Africa from Fort Lee, VA, in January 1993 for 70 days during the United Nations humanitarian mission called Operation Restore Hope. At first, I was to join my officer in charge (OIC) and his boss, the director of the Petroleum and Water Department at Fort Lee, VA, as a technical advisor “in town” in Mogadishu. My OIC phoned from Somalia to say they didn’t need me, but to deploy from Fort Lee with the 240th Quartermaster Battalion. I was to assist this pipeline and terminal operating battalion with water operations.

When we arrived 19 Jan 93 “on the airfield” in Mogadishu, Somalia, we did not have a place to stay. After about a week, we finally set up camp. About two days later, higher headquarters wanted to send me to southern Somalia to check out a 600-gallons per hour (gph) reverse osmosis water purification Unit (ROWPU) while the 240th stayed in Mogadishu.

Later that night, about 2300 hours, I was told that I was to be NCOIC for a logistics support activity in Jilib, a small village south of Mogadishu. Since I only had a rucksack packed, I ended up taking everything. The convoy was set to leave the next morning at 0730 hours. I met the convoy commander who was the logistics support activity OIC (CPT S. Carter Corsello) when he got into my truck. We finally left Mogadishu 28 Jan 93 for Jilib with 29 vehicles and enough food, water and fuel to get started.

We encountered several breakdowns and mechanical problems with vehicles on the 215-mile trip that took 17 hours. The Engineers were building a road network into the heartland of Somalia so that non- government organizations could get food and other aid to local citizens. Our logistics support activity had four basic functional areas: water purification; maintenance; petroleum, oils and lubricants (POL); and Class I (rations). Our mission was to support about 1,350 soldiers of the 36th Engineer Group from Fort Benning, GA, and provide backup support for the 10th Mountain Division soldiers in the area. Our 56 soldiers came from 9 different companies, 2 battalions and the group headquarters.

The roads from Mogadishu to Jilib had been cleaned up by the Engineers, but were still terrible. We arrived about 0330 hours, covered with red dust from the roads. After finding everyone somewhere to sleep in abandoned buildings, we went to sleep about 0500 hours. We were awakened by an officer from S3 about 0630 to begin the day.

First thing, we surveyed the proposed site for the entire logistics support activity. We had to locate a site large enough for the three 20,000-gallon collapsible fuel tanks and the Class I section. We laid out what we wanted, and the engineers began to clear the area with bulldozers.

After a day, we moved in our vehicles to set up the 60,000-gallon field fuel distribution system. The Class I section was put in a building at the end of the logistics support activity site. A human remains had to be moved from the building where we were to sleep.

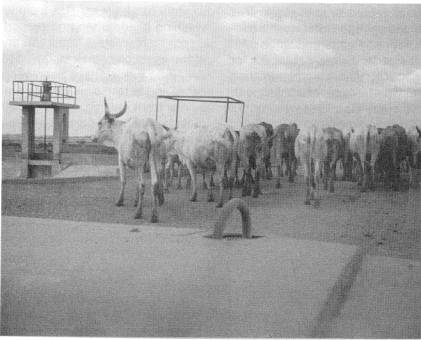

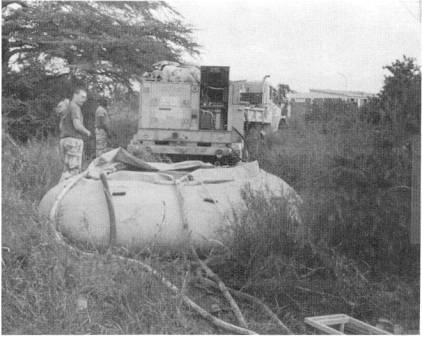

The next convoy of 14 soldiers arrived in Jilib about three days later with two 600-gph ROWPUs. One ROWPU was trailer-mounted (U.S. Army equipment) and the other was skid-mounted (U.S. Marine water purification equipment). We sent one ROWPU to an irrigation canal about 12 miles south of our logistics support activity. The intake was from surface water, and this canal site was infested with little gray bugs. The only place to move was where cattle crossed daily.

The NCOIC of the water section spoke to the preventive medicine personnel about the site, but at the time there were no alternate sites. The wells at Jilib were too deep to draw water from. Preventive medicine approved the site with no other choice. I went to survey the site and told my OIC to try and hurry the Engineers up to complete the well head at the newly proposed site.

A well at Bandar Salom in the Jilib area became the new site after Navy engineers tested and completed it for water production. The Bandar Salom well had to be fitted with a sump pump to get the water out. The pump only produced about 16 gallons per minute (gpm), and the ROWPU needs 27 to 33 gpm coming into it. We placed a 3,000-gallon collapsible tank next to the well, filled the tank with water, and pumped the water into the ROWPU for purification. Operations continued for two or three hours before using all the water in the tank. This provided enough water for this mission with a 14 gpm production rate. I left Bandar Salom 6 Mar 93 for Mogadishu, where I was assisting 240th Quartermaster Battalion with water operations “in town” until I left Somalia 1 Apr 93.

In a harsh environment such as Somalia. soldiers have to be very sanitary at all times. This includes washing hands often and properly disposing of waste. Malaria was one of the worst problems experienced. Everyone was to have been vaccinated and to take a pill weekly. One soldier from my unit ended up with malaria. About 50 personnel in our operational area became sick from this disease. Deployed units were to take additional pills after return to the United States.

Caution should be taken when dealing with site selection. Many personnel could get sick from drinking contaminated water. Only the best sites should be used as possible water sites.

Even though enough water purifications units were in country and the units were meeting mission requirements, people were still drinking bottled water. I think that military personnel began depending on bottled water in the Persian Gulf during Operation Desert Shield/ Storm. However, the water we purified in Somalia had fewer total dissolved solids (less salt concentration) than the bottled water. It was also cheaper to purify the water than to purchase bottled water. However, after seeing operations firsthand. I believe that bottled water will continue to augment water supply.

At the time that this article was written in 1994, SFC Kenneth E. Price, Jr. was an Instructor/Writer for the Water Training Division, 262d Quartermaster Battalion, Fort Lee, Virginia. His previous assignments include 307th Engineer Battalion and 407th Supply and Transportation Battalion, Fort Bragg, North Carolina; and 558th United States Army Artillery Group, Elefsis, Greece.