Recovery in 1959 of B-24 Bomber crew lost in Libyan Desert in 1943

Story of the 1959-60 search for and recovery of crew members of the B-24 Bomber Lady Be Good. This aircraft was discovered in the Libyan Desert 16 years after it lost its way back from a World War II mission to bomb Naples, Italy on 4 April 1943. The plane was found in 1959 by an oil exploration team, miraculously preserved by the desert environment. The next year the bodies of eight of the nine crew members were recovered by Quartermaster Graves Registration personnel.

The U.S. Army Quartermaster Museum at Fort Lee, Virginia maintains a display of items recovered during this operation in its Mortuary Affairs Gallery.

Dedication

This page is dedicated to the crew of the Lady Be Good,

514th Squadron, 376th Bomb Group, 9th Air Force:

1st Lieutenant William J. Hatton, Pilot Whitestone, New York

2d Lieutenant Robert F. Toner, Copilot North Attelboro, Massachusetts

2d Lieutenant Dp Hays, Navigator Lee’s Summit Missouri

2d Lieutenant John S. Woravka, Bombardier Cleveland, Ohio

Technical Sergeant Harold J. Ripslinger, Flight Engineer Saginaw, Michigan

Technical Sergeant Robert E. LaMotte, Radio Operator Lake Linden, Michigan

Staff Sergeant Guy E. Shelley, Gunner/Asst Flight Engineer New Cumberland, Pennsylvania

Staff Sergeant Vernon L. Moore, Gunner/Asst Radio Operator New Boston, Ohio

Staff Sergeant Samuel R. Adams, Gunner Eureka, Illinois

World War II – 4 April 1943

It was after noon on 4 April 1943 the B-24D bomber Lady Be Good departed Soluch airstrip on the coast of Libya, with her crew of nine on their first combat mission. This was a high altitude bombing run on the port at Naples, Italy. Lady Be Good turned back 30 minutes before the target either due to poor visibility or engine problems caused by sand at the takeoff site.

The aircraft was flying above cloud cover and at night. There are several theories as to how the aircraft became lost. Strong tail winds, navigational errors and a lack of visibility of the ground being the most probable. The official Graves Registration Report of Investigation states:

“The aircraft flew on a 150 degree course toward Benina Airfield (Libya). The craft radioed for a directional reading from the HF/DF (high frequency/direction finding) station at Benina and received a reading of 330 degrees from Benina. The actions of the pilot in flying 440 miles into the desert, however, indicate the navigator probably took a reciprocal reading off the back of the radio directional loop antenna from a position beyond and south of Benina but ‘on course’. The pilot few into the desert, thinking he was still over the Mediterranean and on his way to Benina.”

The Lady Be Good was the only aircraft that did not return from that mission. Air-Sea Rescue conducted an extensive search, concentrating on the sea. No evidence of the crew or aircraft were found.

Photo of aircraft taking off on 4 April 1943 mission to Naples, Italy.

Crash Site Discovery – 1958

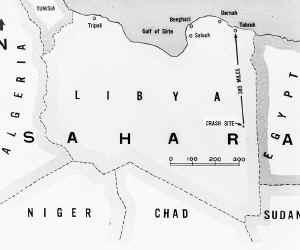

Fifteen years later in May 1958 the Lady Be Good was spotted during an aerial survey by a British oil exploration team from the D’Arcy Oil Company (later to become part of British Petroleum). In March 1959 a D’Arcy ground geological team visited the aircraft. The aircraft was located on a featureless gravel plain in the Libyan Desert near the edge of Sand Sea of Calanscio. This was approximately 440 miles south of Soluch, Libya.

The Lady Be Good had skidded almost 700 yards, the stress of the crash breaking the body of the aircraft just behind the main wings. The propellers on engines 1, 2, and 3 had been feathered and not under power when the plane crashed. The aircraft was intact despite the crash landing and was in an excellent state of preservation. An example of this was that the recovery crew was able to fire one of the bomber’s 50 caliber machine-guns simply by pulling the trigger. A radio was removed from the Lady Be Good and installed in a C-47 cargo plane involved in the operation. The C-47s radio had failed on the flight to the crash site, the replacement radio worked perfectly.

The rear escape hatch and the bomb bay doors of the aircraft were open and no parachutes or “Mae West” life preservers were found on the bomber. It was assumed that the crew had parachuted shortly before the crash.

Ground Search for Crew – 1959

Upon return from visiting the Lady be Good in March 1959, D’Arcy surveyor Gordon Bowerman wrote his friend Lieutenant Colonel Walter B. Kolbus, commander of Wheelus Air Base, Libya about the discovery of the bomber. Mr. Bowerman’s letter contained information from the plane’s maintenance inspection records and crew names found on clothing and equipment in the aircraft. This contact resulted in notification of the U.S. Army Quartermaster Mortuary System in Frankfurt, Germany which was responsible for identification and recovery of deceased military personnel.

In May 1959, a small investigation team consisting of Captain Myron C. Fuller and a civilian anthropologist Mr. Wesley A. Neep, from the Quartermaster Mortuary in Frankfurt, Germany were sent to Libya to search for the remains of the crewmen. This team conducted an extensive ground search and ground controlled air search near the crash site from May to August 1959. This effort was assisted by Air Force personnel from Wheelus Air Force Base near Tripoli, Libya and a civilian contractor which provided ground transportation and local labor.

During the search, items of equipment and several improvised arrowhead markers were found on an old trail leading northwest. The first items found were a pair of rubber flight boots with fleece lining which had the toes pointed in an arrow facing north. These were found 19 miles north of the crash site near the the vehicle tracks left by a WWII convoy. The arrowhead markers were made from parachutes weighed down with stones, presumably to mark the crew’s trail in an attempt to lead Air-Sea Rescue to their location. Not far north of the last parachute found were the shifting sands of the vast sand sea of Calanscio. Despite months of searching no remains were found. In the words of the search team leaders, “The search was abandoned when equipment began to deteriorate and fail and the probability of the airmen being completely covered by shifting sand made the dangers of further search impractical.”

Five Crewmembers Found – 1960

On 11 February 1960 the remains of five crew members were found on a plateau inside the sand sea by British Petroleum employees searching for oil. The five remains were closely grouped in an area littered with canteens, flashlights, pieces of parachutes, flight jackets, and other readily identifiable bits of equipment and personal effect.

A diary belonging to Lieutenant Robert Toner was found among the effects. His short poignant diary entries for the eight days from 5 to 12 April 1943, told a remarkable story of the airmen’s courage and superhuman efforts to survive. It established the fact that the crew bailed out at 2:00 A.M. on 5 April 1943; that Lieutenant John S. Woravka, the bombardier, failed to join the main team after bailout; that eight of the crew members trekked 85 miles north to the point at which the remains were found; and that Sergeants Shelley, Moore and Ripslinger continued on in search of help while Lieutenants Hatton, Toner, Hays and Sergeants Adams and LaMotte waited, too exhausted to continue. The eight men had only half a canteen of water among them during their crossing of a desert which reached 130 degrees Fahrenheit at midday. Desert survival experts had predicted before the remains were found that the airmen could only have moved 25 or 30 miles on foot.

Captain Fuller and his team members returned to Libya a few days after the discovery and the five crewmembers and their personal effects were collected and flown to the Army Quartermaster Mortuary at Frankfurt, Germany, for processing to establish positive identification.

Final Search for Crew “Operation Climax”- 1960

After the discovery of the five airmen and the accompanying media interest, a final, more extensive, search and recovery operation was launched. This effort had a 19 member search party with six vehicles and two light helicopters to search for the four remaining crewmembers. Accompanying the search party was a 4 member Army Public Information Group to take still photographs and motion pictures. This was a joint Army/Air Force partnership operation..

Air Force RF-101 reconnaissance fighters few high altitude photo missions of the search areas to assist in the search effort. The search party and their equipment were flown into the desert on an Air Force C-130 cargo plane. An extensive ground-controlled air search was conducted.

On 12 May 1960, a British Petroleum Company work party in the area discovered Staff Sergeant Guy E. Shelley 21 miles northwest of the location of the first five crewmembers.

On 17 May, one the the helicopters conducting an air sweep spotted the remains of Technical Sergeant Harold J. Ripslinger on the eastern slope of a high dune. He had been located an additional 26 miles north of Sergeant Shelley. The area was characterized by a labyrinth of 600 foot sand dunes.

Operation Climax ended in late May 1960 after additional unsuccessful searches for the remaining two airmen.

In August 1960 another British Petroleum team discovered remains of Lieutenant John S. Woravka who had failed to link up with the other eight. His remains were found about 12 miles north north-east of Lady Be Good. He was still in his full high altitude flying suit with parachute attached. It appears that his parachute failed to open properly and he perished at his landing site. The Air Force dispatched a team that recovered the airman without Army assistance. Air Force personnel sent to recover Lieutenant Woravka found discarded parachute harnesses and high altitude flight clothing marking the bail out site for the remaining crew less than half a mile southwest of Woravka.

Unfortunately, one crew member, Staff Sergeant V.L. Moore was not found. At the end of this massive search operation, search teams had covered an area of approximately 6,300 square miles.

Epilogue

Life magazine published an article on the Lady Be Good in their March 7, 1960 issue. At least two books and numerous newspaper and magazine articles have been devoted to this subject.

Various items from the Lady Be Good went to the Air Force Museum, Air Force Academy and the Army Quartermaster Museum. Souvenirs were also removed from the aircraft by search party members and various oil exploration teams passing though the area.

In April 1968 a Royal Air Force Desert Rescue Team visited the crash site and recovered 21 items, including an engine, for study by McDonnell-Douglas Aircraft Corporation. This was in part partly prompted by the desire to understand the possible effects of long term storage on intercontinental ballistic missiles. The engine and many of the other components were later donated to the Air Force Museum.

By the early-1970s the Lady Be Good had been stripped down to the frame by oil exploration teams and various souvenir hunters. What remains of the aircraft was removed from the desert in August 1994 by the Libyan government, under the direction of Dr. Fadel Ali Mohamed, Controller of Antiquities, Cyrene, for safekeeping at a military barracks in Tobruk.

Wheelus Air Force Base, Libya, which supported search and recovery operations, dedicated a beautiful stained glass window at their chapel to the Lady Be Good crew. Funds for the design and manufacture of the window were donated by USAF personnel of the 7272nd Air Base Wing stationed at Wheelus AFB. The window, designed by German artist, Peter Hess, was unveiled in January 1961. With the closure of Wheelus AFB in 1971 the window was sent to the U.S. Air Force Museum at Wright Patterson, Air Force Base, Ohio.

Lady Be Good Exhibit – Army Quartermaster Museum

In April and November 1960, the Army Quartermaster Museum at Fort Lee, Virginia received a number of U.S. Government issue items of uniform and equipment found on or in the vicinity of crew members by Quartermaster Graves Registration personnel during search efforts. These items include bits of parachute, a flight jacket, shoes, belts, caps, flashlight, batteries, two watches, a canteen, a survival map, life vest and part of a survival kit containing eight squares of carmel. Many of these items are on display in the museum’s Mortuary Affairs exhibit dedicated to the Lady Be Good.

In 1968 the museum loaned several of the items to the McDonnell Douglas Corporation for analysis of the desert’s effect on these items. The flashlight and “Mae West’ life vest showed evidence of erosive effect from blowing sand. The Army issue Elgin A-11 wrist watch still ran and was accurate to within 10 seconds per day. The survival map, which was British issue, was tested for fading and shrinkage.

Other Sources of Information on Lady Be Good

Books

Birdsal, Stevel, Log of The Liberators, An Illustrated History of the B-24 Contains several pages of photos of LBG

Breuer, William B., Unexplained Mysteries of World War II John Wiley& Sons, Inc., NY, 1997. pp 160-162. Contains a small section on LBG, erroneously states that the crewmembers were never found.

Jackson, Robert. Unexplained Mysteries of World War II. NY: Gallery, 1991. pp. 6-11. D743.9J32

Martinez, Mario. Lady’s Men; The Saga of Lady Be Good and her Crew. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis Maryland, 1995, 208 p. Updated story of LGB with extensive interviews of the oil men who located and first visited the aircraft.

McClendon, Dennis E. The Lady Be Good: Mystery Bomber of WWII. NY: Day, 1962. 192 p. D790M34. First book on the LBG, reissued by Aero Publishers, Fallbruck, CA with a new epilogue in 1982.

Walker, James W. The Liberanos: WWII History of the 376th Bomb Group. Waco, TX: 376th Vets Assoc, 1994. 613 p. D790.14-376thB-W27. Chapter 8, “Lady Be Good: The Desert Ghost” pp. 219-281 gives an extensively researched account of the last mission, discovery and crew recovery of the LBG.

Magazines

Ali Mohamed, Dr. Fadel, “The Return of the Lady Be Good” After the Battle (No 89), pp. 28-31 Author describes removal of the LBG from the desert in August 1994 by the Libyan government for safekeeping in Tobruk.

Billet, A.B., “Natural Environmental Effects On Material After Long Exposure.” Test Engineering, p. 20-27, February 1967 Article contains short citation on testing of items removed from the Lady Be Good.

Hanna, William. “The Ordeal of the Lady Be Good.” American History Illustrated 16 (Nov 1981): pp. 8-15. Per. Very readable short account of the LBG story.

Holder, William G. “Epitaph To The Lady–30 Years After” Air University Review, p. 42-50. Widely reprinted in other magazines under a number of different titles, such as “The Mysterious Curse of the Lady Be Good” in B-24 Liberator Magazine. Includes a small section on “jinx” incidents involving the LBG.

Life Magazine, March 7, 1960 (Vol 48, No. 9) “17-Year Mystery of the ‘Lady Be Good’, Desert Gives Up Its Secret” First major article on the discovery of the LBG and crew.

“The Lady Be Good.” After the Battle (No 25, 1979): pp. 26-49. Per.

Wright, Donald C., “Last Flight of the Lady be Good” The Retired Officer Magazine, September 1977, pp. 22-26

Newspaper Articles

Burnes, Robert, “WWII Mystery Still Stirs Curiosity,” Kansas City Star, May

30, 2001 Story on Kansas City native, 2nd Lt. D.P. Hays, the much criticized navigator of Lady Be Good.

Gordon, Robert, “Lady Be Good Items on Display at Ft. Lee”, Richmond Times-Dispatch June 28, 1960

Grossman, Lt. Don, “Last Chapter of “Lady Be Good” Story Displayed Here at the QM Museum”,

The (Fort) Lee Traveller, Petersburg, Va, July 1, 1960

Unpublished Documents

Report of Investigation, U.S. Army Quartermaster Mortuary System, Europe, Case: B-24 bomber lost 4/5 April 1943 and the 1959 Libyan Desert search for the nine missing crewmembers. 17 November 1959, Captain Myron C. Fuller, Jr. and Wesley A. Neep.

Report of Investigation, U.S. Army Quartermaster Mortuary System, Europe, Case: Final search for four unrecovered airmen of B-24 Bomber “Lady Be Good” lost April 1943 in the Libyan Desert. 20 June 1960, Captain Myron C. Fuller, Jr. and Wesley A. Neep.

Television

“Lady Be Good”, Armstrong Circle Theater, CBS, date unknown (1959 or 60)

“King Nine Will Not Return” Twilight Zone episode, , Writer; Rod Serling, Second Season 1960-1961. After crashing in the desert, a bomber pilot (Cummings) is haunted by the images of his dead crew. (Fictional, not specifically about “Lady Be Good”)

Ghost Plane of the Desert, “Lady Be Good”, The History Channel, Premiered February 7, 2000.

Movies

We do not know of any feature films relating to the “Lady Be Good” story.

The Sole Survivor, TV Movie, 1969; 1 hour, 40 min.,William Shatner as Lieutenant Colonel Josef Gronke, Richard Basehart as Brigadier General Russell Hamner, Loosely based on “Lady-Be-Good”. Filmed using a wrecked B-25J on El Mirage Dry Lake in California.