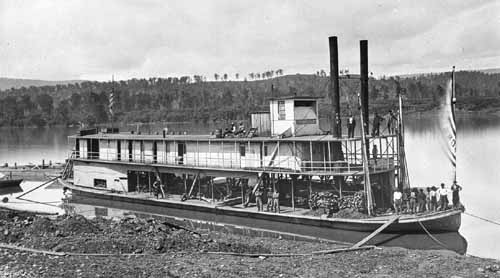

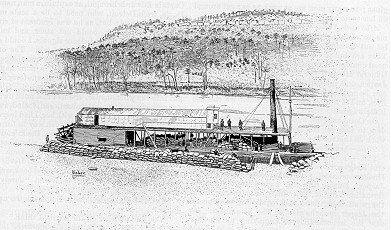

The Story of the USS Chattanooga, a “home-made” steamboat built by the Quartermaster Department in October 1863 to carry supplies to General Grant’s starving army at Chattanooga, Tennessee. As told by Assistant Quartermaster William Le Duc, who “commanded” the Chattanooga.

In answer to the urgent demand of Rosecrans for reinforcements, the Eleventh Corps (Howard’s) and the Twelfth Corps (Slocum’s) were sent from the east to his assistance under command of General Hooker. Marching orders were received on the 22d of September, and the movement was commenced from the east side of the Rappahannock on the 24th; at Alexandria the troops and artillery and officers’ horses were put on cars, and on the 27th started for Nashville. On the 24 of October the advance reached Bridgeport, and on the 3d Hooker established headquarters at Stevenson, and Howard the headquarters of the Eleventh Corps at Bridgeport, then the limit of railroad travel, eight miles east of Stevenson.

The short reach of 26 miles of railroad, or 28 miles of road that ran nearly alongside the railroad, was now all that was necessary for the security of the important position at Chattanooga. But Rosecrans must first secure possession of the route, and then rebuild the long truss-bridge across the Tennessee River, and the trestle, one-quarter of a mile long and 113 feet high, at Whiteside, or Running Water, which would take longer than his stock of provisions and forage would last.

To supply an army of 40,000 or 50,000 men, having several thousand animals, in Chattanooga, by wagons, over country roads 28 miles long, in winter, would be a most difficult, but not an impossible task. Rosecrans determined to build some small, flat bottomed steamers, that could navigate the river from Bridgeport, and transport supplies to Kelley’s Ferry or William’s Island (either within easy reach from Chattanooga), which would enable him to supply his army with comfort until the railroad could be repaired. The enemy held Lookout Mountain, commanding both river and railroad above William’s Island. This position was then deemed impregnable. The Confederates also had an outpost on Raccoon Mountain, commanding the river completely and also overlooking a road that skirted the river-bank on the north side for a short distance, thus making the long detour over Waldron’s Ridge necessary to communication between Stevenson, Bridgeport, and Chattanooga. The river, where it passes through the Raccoon Range, is very rapid and narrow; the place is known as the Suck, and in navigating up stream the aid of windlass and shore-lines is necessary. Kelley’s Landing, below the Suck, is the debouchment of a low pass through Raccoon Mountain, from Lookout Valley, and is within eight or ten miles of Chattanooga.

At Bridgeport I found Captain Edwards, Assistant Quartermaster, from Detroit, preparing to build a steamboat to navigate the river, by mounting an engine, boiler, and stern-wheel on a flat bottomed scow, to be used in carrying and towing up supplies until the completion of the railroad.

I quote from my Diary:

Oct. 5, 1863.-General Hooker was over yesterday . . . and examined the little scow. He appreciated the probable importance of the boat, and ordered me to take it in hand personally and see that work was crowded on it as fast as possible. . . . We also looked over the grade of the Jasper Branch Railroad, which is above high-water mark, and must be used if supplies are sent on the north side of the river. He directed me to send him a report in writing, and a copy for General Rosecrans, of my observations and suggestions, and to go ahead and do what I could without waiting for written orders. I turned my attention to the boat. Captain Edwards has employed a shipbuilder from Lake Erie-Turner, an excellent mechanic, who has built lake vessels and steamers, but who is not so familiar with the construction of flat bottomed, light-draught river steamers. He has a number of ship and other carpenters engaged, with some detailed men from our own troops, making an efficient force. Men who can be serviceable as rough carpenters are abundant; not so with calkers, who will soon be needed, I hope. The frame of the boat is set on blocks, and is only five or six feet above the present water of the river. This mountain stream must be subject to sudden floods, which may make trouble with the boat.

Oct.16.- . . . I found Turner, the master mechanic, in trouble with the hull of the little boat. The planking was nearly all on, and he was getting ready to calk and pitch her bottom when I went to Stevenson. The water had risen so rapidly that it was within sixteen or eighteen inches of her bottom planks when I returned, and Turner was loading her decks with pig-iron that the rebels had left near the bridge-head. He thought he would thus keep the hull down on the blocking, and after the waters went down would then go on and finish.

“But,” I said, “Turner, if the planking gets wet, you cannot calk and pitch until it dries.” “That’s true; and it would take two weeks, and may be four, to dry her after she was submerged, and who knows how high it may rise and when it will abate!” “Then, Turner, what’s the use of weighing it down with pig-iron. Rosecrans’s army depends on this little boat: he must have supplies before two weeks, or quit Chattanooga. Can’t you cross-timber your blocks, and raise the hull faster than the water rises?” “No; I’ve thought of that, and believe it would be useless to try it. Captain Edwards and I concluded the only thing we could do was to weigh it down with pig-iron, and try to hold it, but if the water rises very high it will be swept away, pig-iron and all….. . I went rapidly over to Edwards’s tent . . . and found him in his bunk, overcome by constant work, anxiety, and despair. . . In answer to my question if nothing better could be done than weigh the hull down with pig-iron he said, “No; I’ve done all I can. I don’t know what the water wants to rise for here. It never rose this way where I was brought up, and they’re expecting this boat to be done inside of two weeks, or they will have to fall back!” I turned from his tent, and stood perplexed, staring vacantly toward the pontoon-bridge. I saw a number of extra pontoons tied to the shore – flat bottomed boats, 10 to 12 feet wide and 30 feet long, the sides 18 inches high. I counted them, and then started double-quick for the boatyard, halloing to Turner, “Throw off that iron, quick! Detail me three carpenters: one to bore with a two-and-half or three-inch anger, and two to make plugs to fill the holes. Send some laborers into all the camps to bring every bucket, and find some careful men who are not afraid to go under the boat and knock out blocks as fast as I bring them down a pontoon.”

Turner, who had been standing silent and amazed at my excitement and rapid orders, exclaimed, with a sudden burst of conviction, “That’s it! That’s it! That’ll do! Hurrah! We’ll save her yet. Come here with me under the boat, and help knock out a row of blocks.” And he jumped into the water up to his arm-pits, leaving me to execute my own orders. The pontoons were dropped down the river, the holes were bored in the end allowing them partly to fill, and they were then pulled under the boat as fast as the blocks were out. The holes were then plugged. and the water was dipped until they began to lift up on the bottom of the hull, and when all were under that were necessary, then rapid work was resumed with the buckets, till by 2 o’clock in the morning she was safely riding on the top of the rising waters. They are now calking and pitching her as rapidly as possible, and fixing beams for wheel and engines; as many men are at work as can get around on her to do anything.

Afternoon 16th.- General Howard rode out with me to examine the bridge work on Jasper road, let out to some citizens living inside our lines. They are dull to comprehend, slow to execute, and need constant direction and supervision. Showed General Howard the unfinished railroad grade to Jasper, and my estimate of the time in which it can be made passable for (rail) cars if we can get the iron (rails), and if not, of the time in which we can use it for wagons.

On October 19th, under General Rosecrans’s orders to General Hooker, I was charged with the work on this road.

20th.- Commenced work on the Jasper branch.

22d.- General Grant and Quartermaster General Meigs arrived on their way to the front with Hooker and staff. I accompanied them as far as Jasper. During the ride I gave Grant what information I had of the country, the streams, roads, the work being done and required to be done on the Jasper branch, also on the steamboat. He saw the impossibility of supplying by the dirt road, and approved the building of the Jasper branch, and extending it if practicable to Kelley’s; also appreciated the importance of the little steamboat, which will be ready for launching tomorrow or Saturday. General Meigs . . . approved of the Jasper branch scheme and gave me a message ordering the iron forwarded at once.

23d.- Steamboat ready to launch tomorrow. Railroad work progressing.

24th.- Steamer launched safely.

26th.-Work on boat progressing favorably; as many men are at work on her as can be employed.

Extract from a letter dated Nov. 1st, 1863:

I had urged forward the construction of the little steamer day and night, and started her with only a skeleton of a pilot house, without waiting for a boiler-deck, which was put on afterward as she was being loaded. Her cabin is now being covered with canvas. On the 29th she made her first trip, with two barges, 34,000 rations, to Rankin’s Ferry, and returned. I loaded two more barges during the night, and started at 4 o’clock A. M. on the 30th for Kelley’s Ferry, forty-five miles distant by river. The day was very stormy, with unfavorable head-winds. We made slow progress against the wind and the rapid current of this tortuous mountain stream. A hog-chain broke, and we floated down the stream while repairing it with help of block and tackle. I ordered the engineer to give only steam enough to overcome the current and keep crawling up, fearful of breaking some steam-pipe connection, or of starting a leak in the limber half-braced boat. Had another break, and again floated helplessly down while repairing; straightened up once more, and moved on again-barely moved up in some places where the current was unusually strong; and so we kept on, trembling and hoping, under the responsibility of landing safely this important cargo of rations. Night fell upon us–the darkest night possible–with a driving rain, in which, like a blind person, the little boat was feeling her way up an unknown river.

Captain Edwards brought, as captain, a man named Davis, from Detroit, who used to be a mate on a Lake Erie vessel; but, as he was ignorant of river boats or navigation, could not steer, and knew nothing of wheel-house bells or signals, I could not trust him on this important first trip. The only soldier I could find who claimed any knowledge of the business of a river pilot was a man named Williams, who had steered on a steam-ferry running between Cincinnati and Covington. Him I put into the wheel-house, and as I had once owned a fourth interest in a steamboat, and fooled away considerable money and time with her, I had learned enough of the wheel to know which way to turn it, and of the bell-pulls to signal Stop, Back, and Go ahead. I went with Williams into the wheel-house, and put Davis on the bows, to keep a lookout. As the night grew dark, and finally black, Davis declared he could see nothing, and came back wringing his hands and saying we would “surely be wrecked if we did not land and tie up.”

“There’s a light ahead now, Davis, on the north shore.”

“Yes, and another on the south, I think.”

“One or both must be rebels’ campfires.”

We tried to keep the middle of the river, which is less than musket shot across in any part. After a long struggle against wind and tide we got abreast of the first campfire, and saw the sentry pacing back and forward before it, and hailed:

“Halloo! there. What troops are those!”,

Back came the answer in unmistakable Southern patois: “Ninth Tennessee. Run your old tea kittle ashore here, and give us some hot whisky.”

The answer was not comforting. I knew of no Tennessee regiment in the Union service except one, or part of one, commanded by Colonel Stokes, and where that was I did not know. So we put the boat over to the other shore as fast as possible, and to gain time I called out:

“Who’s in command?”

“Old Stokes, you bet.”

“Never mind, Williams, keep her in the middle. We’re all right.- How far to Kelley’s Ferry?”

“Rite over thar whar you see that fire. They ‘re sittin’ up for ye, I reckon.”

“Steady, Williams. Keep around the bend and steer for the light.”

And in due time we tied the steamboat and barges safely to shore, with 40,000 rations and 39,000 pounds of forage, within five miles of General Hooker’s men, who had half a breakfast ration left in haversacks; and within eight or ten miles of Chattanooga, where four cakes of hard bread and a quarter pound of pork made a three days’ ration. In Chattanooga there were but four boxes of hard bread left in the commissary warehouses on the morning of the 30th [October]. About midnight I started an orderly to report to General Hooker the safe arrival of the rations. The orderly returned about sunrise, and reported that the news went through the camps faster than his horse, and the soldiers were jubilant, and cheering “The Cracker line open. Full rations, boys! Three cheers for the Cracker line,” as if we had won another victory; and we had.

Extracted from: Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. III 1884-1888